New York's Grasslands: A Vital Habitat for Wildlife

by Betsy McCully, Nov. 12, 2018

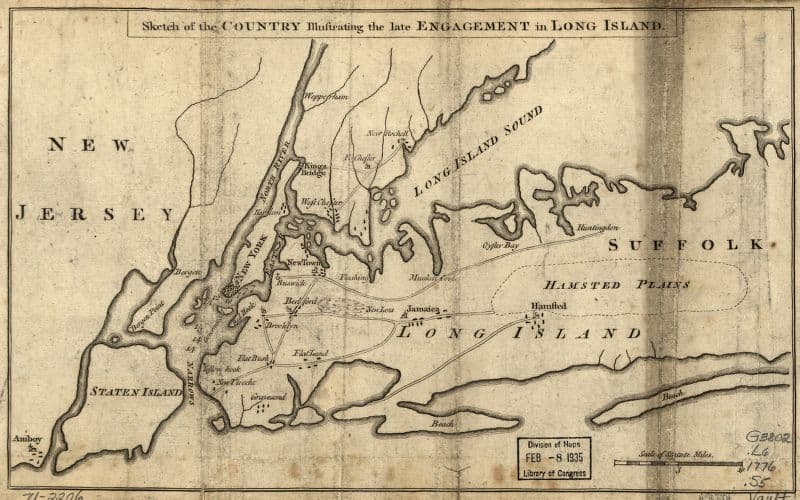

The Hempstead Plains

This whole tract appears as smooth and unbroken as the surface of the sea in a calm, though as you pass over it, you meet with slight undulations, and the views of the traveler over the whole expanse is unobstructed, by tree, or shrub, or any other vegetable production. Within the memory of persons still living, there was scarcely an enclosure in this whole compass….

–Nathaniel Prime, 1845

How the Prairie Evolved

How the Prairie Was Degraded

How the Prairie is being Restored

It represents one of the most rapidly vanishing habitats in the world, along with scores of birds, butterflies, and other animals that are vanishing with it.

–Friends of the Hempstead Plains

Threatened Grassland Flora

Threatened Grassland Birds

New York Grasslands Reading List

McCully, Betsy. City at the Water’s Edge: A Natural History of New York (Rutgers/Rivergate Press, 2007)

New York Grasslands Links

Friends of Hempstead Plains, http://www.friendsofhp.org

c. Betsy McCully 2018-2024