New York Birds: A Comprehensive Guide to Native and Migratory Species

Birds of Ancient New York

In the long-ago time, a hunter lured an eagle to a deer-kill, shot it with his arrow, and stole its feathers. When the Mother of All Eagles saw what the hunter had done, she swooped down, seized him in her great claws, and took him to her eyrie high on a cliff. When Mother Eagle left to find food for her hungry eaglets, the hunter tied up the eaglets’ beaks with a leather thong. Mother Eagle returned and was dismayed to see her eaglets tied up and unable to untie their beaks. So she made a pact with the hunter: She would free him if he untied her eaglets’ beaks and promised never to shoot down eagles again without her permission. The hunter agreed and his descendants have kept his word.

–Iroquois Myth

Birds of Colonial New York

Birds also fill the woods so that men can scarcely go through them for the whistling, the noise, and the chattering.

–Nicolaes van Wassenaer, 1624

Birds Hunted to Extinction and Near Extinction

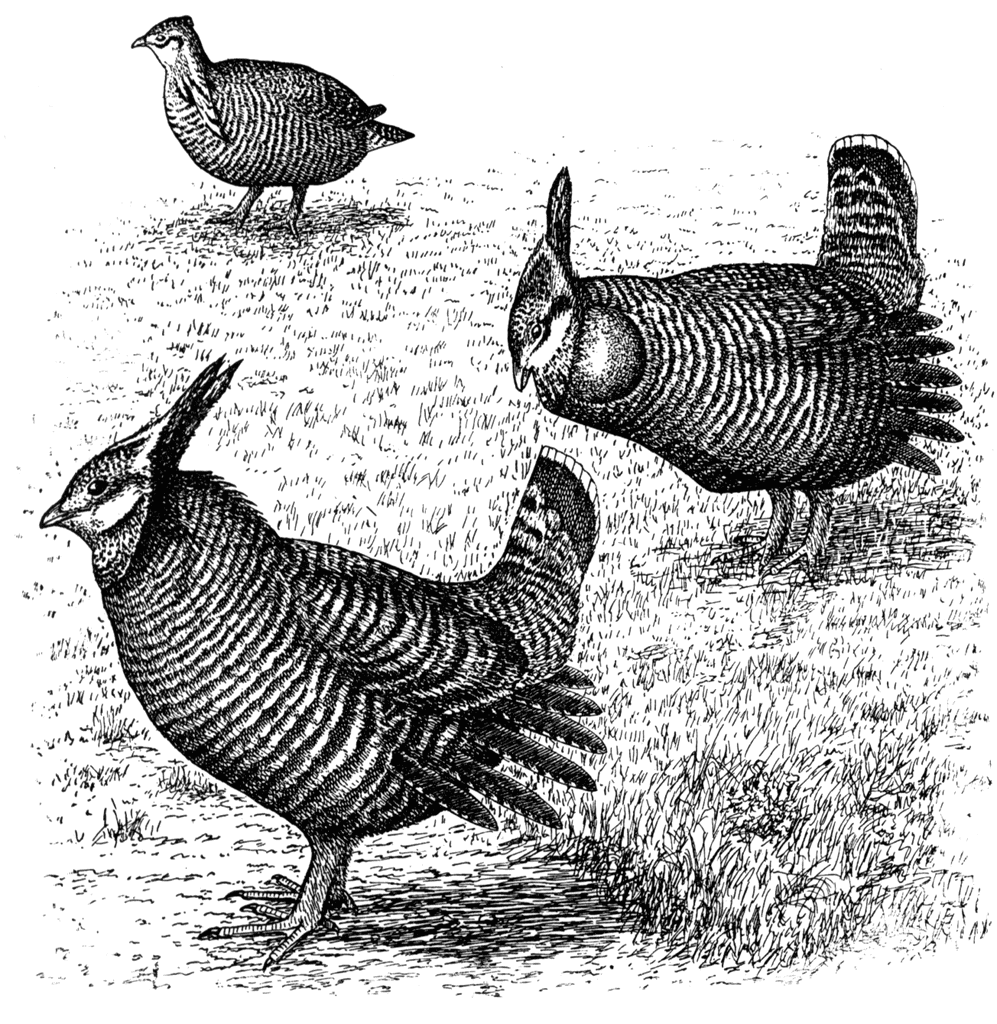

The Heath Hen, Drummer of the Plains

In conversation with several of the elderly residents, they spoke of the “Heath Hen” as being very abundant some twenty or thirty years since, but now consider it entirely extinct.

The Heath Hen, the eastern subspecies of the Prairie Chicken (also called Pinnated Grouse), once inhabited the scrub pine and oak barrens of Long Island and New Jersey. J. P. Giraud, in his 1844 book, The Birds of Long Island (the first book on New York birds), recounts the demise of this once plentiful game bird:

Thirty years ago, it was quite abundant on the brushy plains in Suffolk County. which tract of country is well adapted to its habits — but being a favorite bird with sportsmen, as well as commanding a high price in New York markets, it has been pursued, as a matter of pleasure and profit, until now it is very doubtful if a brace can be found on the island. On a recent excursion over its former favorite haunts, I could find no trace of it. In conversation with several of the elder residents, they spoke of the “Heath Hen” as being very abundant some twenty or thirty years since, but now consider it entirely extinct.

Like its western cousin, it was famous for its mating dances, which involved drumming that could be heard for miles–hence its Latin name Tympanuchus cupido cupido.

The Wild Turkey

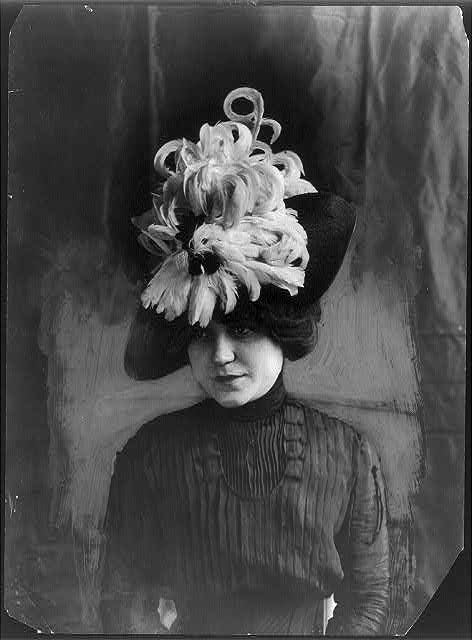

Egrets and the Feather Trade

The place for dead birds is not above a pretty woman’s face.

Environmental Threats to Birds

Rachel Carson alerted the public to the perils of pesticides with publication of her landmark book, Silent Spring, in 1962. Her description of poisoned birds falling from the sky, and her prediction of a future silent spring when we would no longer hear them sing, is unforgettable. In 1964, Roger Tory Peterson, in his “Foreword” to Bull’s Birds of the New York Area, predicted calamitous declines of bird species due to the widespread use of pesticides since World War II. Already, Peterson noted, breeding ospreys on eastern Long Island had declined from 500 nests in 1940 to 75 nests in 1950, and given their continuing decline in the 1960s, he feared their complete extirpation from the region. He also noted that the Peregrine Falcon was gone from the Hudson Valley, compared to pre-1950s reports of a dozen nesting pairs. The Bald Eagle, once abundant in the region, was also extirpated at the time he wrote. All three species were decimated by the widespread application of DDT, which accumulated in the food chain and drastically thinned their eggshells.

Recovery and Protection of Threatened Birds

The question is whether, by 2050, the habitat they need is still going to be here to support them or will we keep whittling away at it so that the habitat disappears?

–Peter Nye, 2004

Only those active observers who have been in the field for the last 30 years or so can appreciate the phenomenal comeback this heron has made.

Wading bird populations on these islands and throughout New York Harbor have been monitored by the NYC Bird Alliance (formerly New York City Audubon Society) since 1982. Their 2016 Report surveyed the nesting species: Great Egret, Snowy Egret, Black-crowned Night Heron, Yellow-crowned Night Heron, Glossy Ibis, Little Blue Heron and Tri-colored Heron. Great Blue Heron and Green Heron nested on mainland sites. They noted that several islands in the Arthur Kill complex had been abandoned altogether for reasons not quite clear, although human disturbance and mammal predation are suspected causes. Since 1993, populations of wading birds declined from 2,233 pairs in that peak year to 1,420 pairs in 2016. For more detailed statistics visit their website and read their annual reports on Harbor Herons.

Where to Find Birds of the New York Region

Because New York City is on the Atlantic Flyway, it is a magnet for neotropical migratory birds, which migrate by the millions every spring and fall. From a bird’s eye view, urban parks look like oases in a concrete desert. Central Park is one of the hotspots for migrating songbirds, especially in what’s known as The Ramble. It’s possible, on a really really good day, to see as many as 30 neotropical warbler species and 100 migratory bird species all-told (or tallied) in a single day from dawn to dusk. To get that many you need the right weather conditions to produce what’s known to birders as a “fallout,” when birds literally drip from the trees. Throughout the year in Central Park, according to NYC Bird Alliance, 192 bird species “are regular visitors or year-round residents and over 88 are infrequent or rare visitors.”

The refuge’s manmade ponds harbor wintering ducks and geese, including Snow Geese, and year-round resident Mute Swans and Canada Geese — so many of the latter, in fact, that they crowd out other waterfowl.

For a detailed guide to visiting birding spots in the five boroughs of New York City, visit the website of NYC Bird Alliance.

A two-hour drive or train ride from Manhattan will take you to Montauk Point on eastern Long Island, where tens of thousands of Common Eiders and Black, Surf, and White-winged Scoters, as well as good numbers of Common Loons and Red-breasted Mergansers, can be seen and heard offshore. Less common are Red-necked Grebes. Occasional rarities show up, such as Common Murres and Razor-bills. Gannets may be seen gliding over the distant waters and dive-bombing for fish.

New York Birds Reading List

Bull’s Birds of New York State. Emanuel Levine, ed. Ithaca: Comstock/Cornell, 1998

Burger, Michael F. and Jillian M. Liner. Important Bird Areas of New York. New York: Audubon New York, 2005

Day, Leslie, Field Guide to the Neighborhood Birds of New York City. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 2015

Rivel, Deborah and Kelly Rosenheim, Birdwatching in New York City and Long Island. Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 2016

New York Birds Links

New York City Bird Alliance:

Brooklyn Bird Club:

New Jersey Audubon:

c. Betsy McCully 2018-2025