New York Wild Flora

by Betsy McCully

Updated February 2026

Wherever they and their domestic animals walked, it seemed, alien plants sprang up. Indeed, the Algonquians dubbed the plantain weed “Englishman’s Foot.”

–Betsy McCully, City at the Water’s Edge: A Natural History of New York, 2007

Wild Flora in Colonial New York

In 1650, Adriaen van der Donck, a Dutch lawyer turned gentleman farmer in New Netherland (New York), made a list of “the healing herbs” he found here. Native herbs he listed included Sweet Flag, Solomon’s Seal, Wild Indigo, Laurel, Snakeroot, Angelica, and Jewelweed; naturalized non-native plants included Common Mullein, English Plantain, Shepherd’s Purse, and Blessed Thistle. (I have used current common names not his nomenclature.) He described the medicinal values of the herbs: “The country is full of all kinds of plants and trees, so that there are undoubtedly numerous good specifics. Experts could do much in that direction, all the more so, we believe, since the Indians are able to heal frightful open wounds and ugly old sores with mere roots, bulbs, and leaves” (Specifics were herbal remedies.)

John Josselyn, an English gentleman with a keen interest in botany and medicine, visited New England in the 1600s, and published the earliest English account of New England’s flora (among other topics of natural history), New England Rarities (1672). He recognized the familiar weeds he knew back home, including Dandelion, Sow-thistle, Shepherd’s Purse, Nettles, Nightshade, English Plantain, Mayweed, Mullein, and Wormwood. He also found many native plants new to the English, and described their medicinal uses among the Indians.

New York Flora, circa 1800s

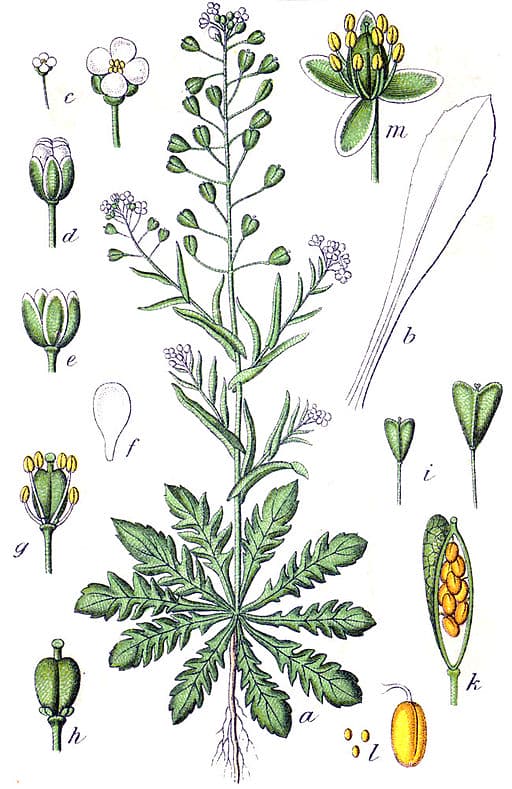

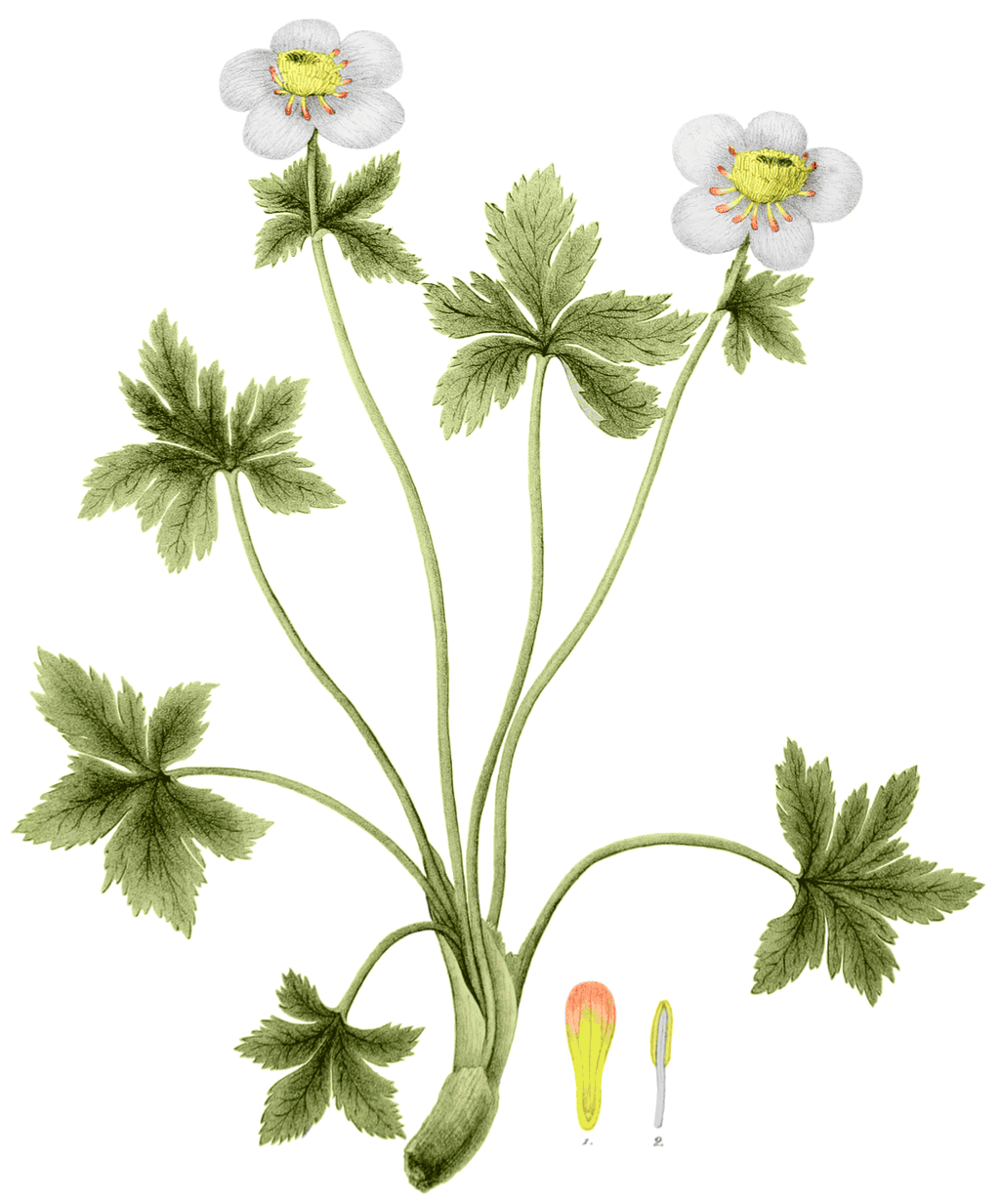

A number of naturalists catalogued New York City’s wild flora beginning in the early 1800s. Samuel Latham Mitchill, physician and surgeon-general of New York State, amassed a private collection of wild plants in the New York City region, listing their known medicinal uses. As president of the Lyceum of Natural History of New York, Mitchill was instrumental in the effort to catalogue the flora of both New York City and State. A census of flora in Manhattan conducted by John Eaton Le Conte in 1811 tallied 450 species (this first publication of naturalist LeConte was written in Latin). Botanist John Torrey collected plants within a thirty-mile radius of Manhattan, assiduously sorting out native from non-native plants, noting their medicinal as well as culinary uses. On Manhattan, he identified many of the grasses of “meadows, parks, lawns, and roadsides” as naturalized European species, including Timothy Grass (Phleum pratense), Fox-tail (Alopecurus pratensis), Crab-grass (Digitaria sanguinalis), Brome Grass (Bromus species), and Bermuda Grass. Other non-native plants included Privet (Ligustrum vulgare), Speedwell (Veronica agrestis), Mullein (Verbascum thapsus), Bittersweet (Solanum dulcamera), Wild Carrot (Daucus carota), Tansy (Tanacetum vulgare), and Shepherd’s Purse (Thlaspi bursa-pastoris). (I have used Torrey’s nomenclature.) He published his catalogue in 1819, listing the plants by their Latin and common names and giving the places where specimens were collected. He also catalogued the flora of New York State in 1843, counting 160 plant species as introduced or naturalized. The count might have been 161 had he known that Clover (Trifolium repens) was non-native; he supposed it to be native because “it springs up everywhere.” Other introduced plants included Berberis vulgaris, Common St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum), and Wild Mustard (Sinapsis arvensis) — a “noxious weed.” A now-rare native wild plant he listed was American Globeflower (Trollius laxus).

Weeds and Invasive Plants in New York

–Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1878

Are all weeds noxious and undesirable?

It all depends on the context. Perhaps you know Emerson’s dictum that “a weed is a plant whose virtues are undiscovered.” Well, a weed may also be a plant whose virtues are forgotten. In the early natural histories of New York and New England mentioned above, there was no mention of weeds; rather, the emphasis was on the medicinal uses of both native and non-native plants. To the American Indian and Euro-American colonist alike, wild plants were sought out for their healing properties. Europeans were keen to learn how American Indians used wild plants to treat various ailments. And no doubt, American Indian healers, usually women, were interested to know how their European counterparts used the introduced herbs they now found in their country. English Plantain is one example. There are native plantain species, and like its cousins, English Plantain offers similar curative aids. So, in calling wild plants that colonize our lawns and gardens weeds because we don’t want them there, we may be overlooking their virtues, both medicinal and edible.

Are there safe alternatives to toxic herbicides?

Our environment is loaded with toxic residues of chemical herbicides and pesticides. Rachel Carson in her classic Silent Spring, written way back in the 1960s, documented the hundreds of chemicals that were poisoning not only our environment — the air we breathe, water we drink, and soil we grow our food in — but our bodies. She questioned what the synergistic effect of all these chemicals combined must be having on our own cells — our body’s ecosystem — as well as on our environment. That was decades ago. As a result of her book, one pesticide, DDT, was banned in our country. One in hundreds, perhaps thousands. Imagine how many chemicals today poison our air, waters, soils, ecosystems, and bodies! A new study is needed to monitor these chemicals.

In the meantime, we must use alternatives to powerful herbicides like Roundup to control weeds. We can choose safe alternatives, from biological controls to old-fashioned hand-weeding and cultivating. I eschewed toxic chemicals when I had a small garden in Brooklyn, and it was a flourishing garden. I didn’t mind pulling weeds. And maybe, as you weed, you might not throw that weed into the compost pile, but into your salad. Dandelion greens. Purslane. Unsprayed of course. But make sure you can identify them! Learn about edible and medicinal wild plants (see my suggested readings below).

Why be concerned about invasive plants?

What can we do about invasive plants?

If you are a gardener, stop planting them. If you are a property owner, try to eradicate them through biological means. Herbicides like Roundup are non-selective and will kill native or non-invasive naturalized plants as well as introduced invasive plants. Herbicides have been used by farmers to kill unwanted “weeds” that may be beneficial to pollinators. Milkweed, the sole host plant for the monarch butterfly, is a prime example. But even weeds considered noxious, such as thistles, attract pollinators that will also pollinate our food plants. You can learn about biological controls by visiting the website of the Center for Invasive Species. And you can get tips on sustainable gardening with native plants from organizations like ReWild Long Island.

Native Flora and Native Habitats

We also need to understand that wild flora, like wild animals, are integral parts of whole ecosystems. Wild plants depend on pollinators to propagate and pollinators such as bees and butterflies depend on wild flora for food. Pollinators like bees may have co-evolved with flowers 90 million years ago! Each species plays a part in an interdependent web of life. Pluck one strand and the whole web collapses.

New York Wild Flora Reading List

Clemants, Steven and Carol Gracie. Wildflowers in the Field and Forest: A Field Guide to the Northeastern United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006

Foster, Steven and James Duke. Field Guide to Medicinal Plants and Herbs of Eastern and Central North America, 3d Ed. Houghton Mifflin, 2014

McCully, Betsy. City at the Water’s Edge: A Natural History of New York (Rivergate/Rutgers University Press, 2007)

Peterson, Lee Allen. Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants of Eastern/Central North America (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1977)

New York Wild Flora Links

ChangeHampton: https://www.changehampton.org

Invasive.org: https://www.invasive.org

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center: https://www.wildflower.org

Long Island Native Plant Initiative: https://www.linpi.org

Native Plant Trust: https://gobotany.nativeplanttrust.org

New York Flora Atlas: http://newyork.plantatlas.usf.edu

New York Natural Heritage Conservation Guides: https://guides.nynhp.org

ReWild Long Island: https://www.rewildlongisland.org

And my personal gallery of New York wildflowers: https://www.newyorknature.us/new-york-wildflower-gallery/

c. Betsy McCully 2018-2026