New York Wildlife

Wildlife in Colonial New York

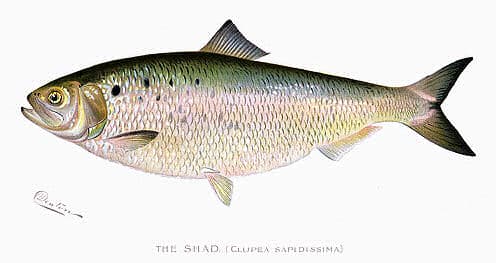

Alewives come up to the fresh rivers to spawn in such multitudes as is almost incredible, pressing up in such shallow waters as will scarce permit them to swim, having likewise such longing desire after the fresh water ponds that no beatings with poles or forcive agitations by other devices will cause them to return to the sea till they have cast their spawn.

—William Wood, New England’s Prospect, 1634

Pre-Colonial Abundance

European Impact

Declines and Recoveries of New York’s Wildlife

Marine Wildlife

Today, the Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica) is considered “ecologically extinct” in the Hudson-Raritan Estuary. Its restoration is considered vital to the health of New York waters, serving as natural water filters and shoreline buffers. In 2009, the New York-New Jersey Baykeeper and the New York-New Jersey Harbor and Estuary Program (HEP) formed the Oyster Restoration Research Partnership (ORRP). That same year, the US Army Corps of Engineers published their draft Hudson-Raritan Estuary Comprehensive Restoration Plan, calling for establishing 200 acres of oyster reefs by 2020 as part of their overall plan. In their final report of 2011, encouraged by the success of oyster planting, ORRP expanded their initial goals from 200 to 500 acres by 2015, and 5,000 acres by 2050. After Superstorm Sandy hit our shores in 2012, oyster reefs came to be seen as a critical buffer against such storms, protecting the city during our era of rising sea levels. In 2014, the NYCDEP received a grant of a million dollars from the Sandy Resiliency Grant Program to build more oyster reefs in Jamaica Bay.

Terrestrial Wildlife

New York Wildlife Reading List

New York Wildlife Links

On marine life:

c. Betsy McCully 2018-2025