New York Woodlands: Exploring Our Diverse Forests

by Betsy McCully

Updated February 2026

We see permanence in the hills we get to know. They do not visibly change, but we can grow up with trees and see them change with us. Since they can outlive us, they connect us to the future and to the places where they grow.

–Berndt Heinrich, The Trees in My Forest, 1997

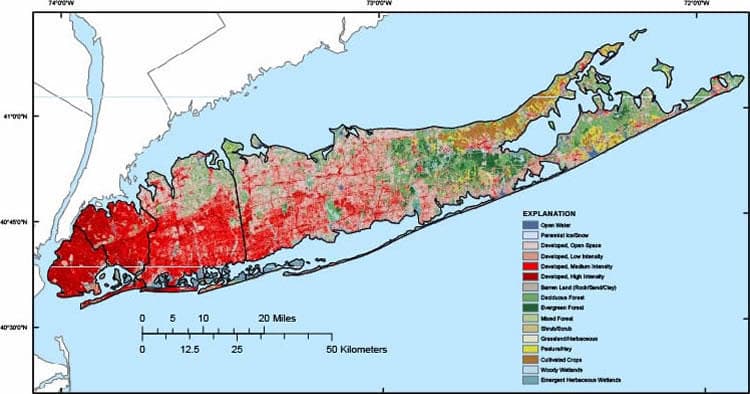

For at least 5,000 years prior to European settlement, it’s estimated that 95% of the Northeastern United States (the Northeast) was covered by forest. A mere 1.5 million acres remain of an original 822 million acres, according to a survey conducted by Mary Byrd Davis in 1993. The thickest forests were north of New York City; our region was a patchwork of forests, wetlands, grasslands, and sand plains, a land long managed by the village-agriculturalists who lived in the region, the Lenape Indians. (For the story of the first New Yorkers, see the page Lenape Native.)

How New York Forests Evolved

How New York Forests Became Degraded

Much of the Hudson Valley was clear-cut every thirty or forty years….

–Robert Boyle, The Hudson River: A Natural and Unnatural History, 1970

In traveling these forests,… you may pass through 5, 6, and even 7 miles of unbroken forest, without discerning a single human habitation, or the least trace of the hand of man except the stumps of felled trees….

–Nathaniel Prime, 1840

How New York Forests Continue to be Degraded

Our native forests and associated biodiversity will melt away, as can already be seen in many places, if we continue to ignore these threats….

Conservation ecologist Emile De Vito published an opinion piece in the New York Times in 2008 warning about the “catastrophic impact” of deer on tree regeneration and forest biodiversity in the New York metropolitan region: “Our native forests and associated biodiversity will melt away, as can already be seen in many places, if we continue to ignore these threats.” Where their numbers have been reduced, and understories allowed to grow back, trees and shrubs are regenerating and birds and wildflowers are returning. To see more photos of our woodland wildflowers and birds, visit my New York Wildflower Gallery and New York Bird Gallery pages.

How New York Forests are being Restored

Where to See the Trees

New York Woodlands Reading List

Barnard, Edward Sibley. New York City Trees: A Field Guide for the Metropolitan Area. NY: Columbia University Press, 2002.

McCully, Betsy. City at the Water’s Edge: A Natural History of New York. Rutgers/Rivergate Press, 2007

McCully, Betsy. Land at the Glacier’s Edge: A Natural History of Long Island from the Narrows to Montauk Point. Rutgers University Press, 2024

New York Woodlands Links

Long Island Pine Barrens Society: https://www.pinebarrens.org

New York City Parks: https://www.nycgovparks.org

c. Betsy McCully 2018-2026